Hadestown and Pyrotheology: old sad stories are good for the soul

"How do you make a musical which brings you into the heart of the difficulties of existence?” - Peter Rollins

A few months ago my friend Deanna invited me to see the musical Hadestown as an early birthday celebration. I knew the show had won ALL the awards and I knew my son was obsessed with it, but I hadn’t listened to the soundtrack or really done any research. All I knew was that it was the doomed story of Orpheus and Eurydice.

I was looking forward to seeing the show even though my love of theater has waned over the years. As someone who has taught and worked in theater the majority of my life, I’m just not as excited by the medium as I once was. When I go to the theater I want to be transformed, confronted by Truth. I want something to be excavated from deep within that had hitherto been lost. I want freaking Greek level purgation and religious experience.

I know I know, I need to adjust my expectations. Before I get into my reaction to Hadestown I need to give you a little background on the last few weeks.

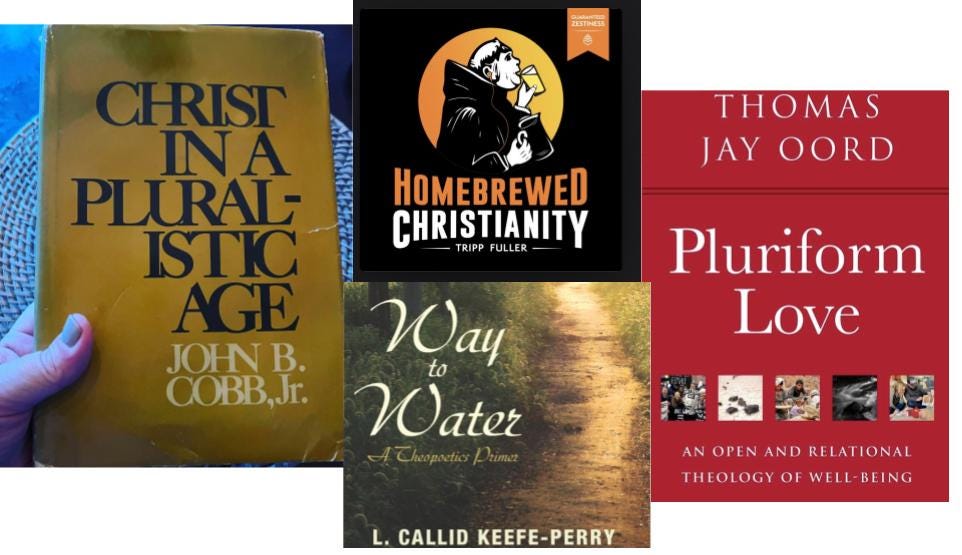

So I’m considering going back to school to study Process Theology. After going back into the Mystics, now I have an itch to go forward into the Philosophers. In working this through I’ve been listening to all the podcasts on process and reading a smattering of books.

One of the words I keep hearing on these podcasts is “theopoetics.” Hmmmm. Sounds promising. So I downloaded Way to Water: a theopoetics primer onto my Kindle and it kinda rocked me.

Theopoetics is basically the work of theology done through the medium of artistic expression as opposed to the rigor of academic analysis. It says that the medium by which we talk about God matters. It opens up the whole conversation of theology to the outsider artist. Incidentally, the term theopoetics was coined by theologian Amos Wilder, Thornton Wilder’s brother.

Read - Our Town: A Requiem for the Common Good - What an old play can teach us about how to take care of our neighbor, November 1, 2021

The Primer itself is rigorous academic study but gives permission to artists as well as theologians to find new and novel ways to fill the gaps in our human story with the Divine. Theopoetics is how I was trained to do theater by a man who saw his job as theater artist as a kind of priest offering sacrament. He understood the religious implications of walking into a theater

Prior to seeing Hadestown yesterday, I listened to a Theopoetics podcast on “Poetics of the Absurd” interviewing the philosopher/radical theologian, Peter Rollins.

I’ve tried to listen to Rollins a few times before and never really grasped his ideas, but this interview was helpful. Think of Rollin’s work as the existential, anti- prosperity gospel. A Bizzarro Joel Osteen. He practices what he terms Pyrotheology - a radical theology of lack; the lack that is original to humans. To be human is to experience this lack. “Underlying antagonism is part of existence. (see #evolution) The good news isn’t that beneath the antagonism there is an underlying harmony; instead, the antagonism IS the good news. It’s not something we need to overcome.”

The antagonism is as creative a force as it is destructive. Like fire. “When we can take the sting out of antagonism,” Rollins argues “we can live a much richer and creative form of life.”

Rollins offers courses in things like Atheism for Lent where one takes on Atheism like a spiritual practice. He offers events that act as de-centering rituals to shake and transform. He creates comic books, film, stand up, performance all meant to “operate on parts of our soul that direct speech can’t touch.” In some ways I think of him as a modern Meister Eckhart, adjusting the form to communicate a deeper truth, shocking us into a deeper understanding of God.

We think we want wholeness, satisfaction, full knowledge. Completion. But, Rollins says, what we really want is Desire itself.

“Pyrotheology helps to transform the doubts and difficulties of daily life into a fuel that ignites a journey into the depth and density of life. Pyrotheology offers an incendiary understanding of faith that has nothing to do with the tired debates between theists and atheists. It uncovers how faith helps us resolutely confront our brokenness, joyfully embrace unknowing, and courageously face the difficulties of life. While this journey into the dark might seem unappealing compared with those who sell the "Good News" of certainty and satisfaction, Pyrotheology exposes how this "Good News" is actually very bad news. Instead revealing that we must tarry with the antagonisms of existence if we wish to see transformation in the personal and political world.” - peterrollins.com

So this interview gave me much clearer understanding of Rollins. But here’s the funny bit, as Pete was talking about all the ways he uses art to communicate these ideas, the interviewer said offhandedly, you should write a musical.

Pete laughed, “It would be very hard to do it. During the Great Depression that’s when musicals became huge because musicals were a way to avoid your suffering and brokenness. Cause they’re all so amazing and miraculous. So the real challenge is how do you make a musical which brings you into the heart of the difficulties of existence?”

A few hours later I thought, Peter Rollins definitely has not seen Hadestown.

The story of Eurydice has been dramatized and inspired poetry innumerable times. Last year Sarah Ruhl’s taut play Eurydice was turned into an opera for the Met. Maya Phillips writes in her review in the NYT that the moment Orpheus turns back to look at Eurydice, “the audience’s collective gasp seemed to shake the grand theater.” The audience had the same reaction, she said in Hadestown. Phillips is herself surprised by the unwitting audience. Don’t we all know the ending? Or maybe that’s the point.

The myth has been kicking around for over two millenniums, after all. Orpheus, the greatest musician of all, marries Eurydice, who dies when she’s bitten by a snake on their wedding day. He descends to the underworld, where the god of the dead offers him another chance at love: He can leave with Eurydice, but only if he walks ahead and never turns around. Here’s that spoiler: Orpheus looks, and Eurydice is damned to Hades forever. - Maya Phillips, Love, Trust and Heartbreak on Two Stages, NYT (January 2022)

Hadestown is set in a New Orleans like jazz bar with a live band tiered into the set. Above, behind a wrought iron balcony, sit Hades and his wife Persephone. Below, Hermes, a silver clad showman, narrates the story of young Eurydice, lost, cold and poor, and the musician, Orpheus, also poor but working to write a song that will bring back the spring and with it, full life and happiness.

Instead of a snake biting Eurydice, it is the cold winds and the promise of comfort and security that entice Eurydice to Hades’ lair, which turns out to be an industrial wasteland of unending labor. When Orpheus descends to bring her back, he must sing for the chance to rescue his love.

We all know how the story ends. Hermes tells us in the opening song, “It’s an old tale from way back when. It’s an old song.. it’s an old song, and we’re gonna sing it again. See, someone's got to tell the tale whether or not it turns out well. Maybe it will turn out this time. . . It's a love song! It's a tale of a love from long ago. It's a sad song. . . It's a sad song! But we're gonna sing it even so . .”

He tells us right at the beginning but we don’t really hear him. We don’t really take in what he’s saying. And then when it gets to the moment, we think, just like Hermes said, “Maybe it will turn out this time.” After two thousand years, maybe this time the ending will change. But it doesn’t change. Orpheus can’t trust that he is good enough, that he is beloved enough to be followed out of hell. That he could not only save Eurydice, but free all those trapped in oppression. What power could a small man who writes songs possibly have?

In the theater when that moment happened, just like Phillips said in her review, the audience gasped. I think I gasped. Not from surprise, but from a collective exhale as we let go our desire that the story somehow be different. An audience of almost 5,000 people sat in a moment of silent, communal grief. This was pyrotheology on a grand scale, and guess what, Peter Rollins, it happened during a musical.

“How are they going to leave us here?” I thought as I sat there stunned. But then Hermes returned and sang a reprisal of Road to Hell, but this time we heard it all. We were primed for it.

It's an old song, and that is how it ends. That's how it goes. Don't ask why, brother, don't ask how he could have come so close. The song was written long ago, and that is how it goes. It's a sad song. It's a sad tale. It's a tragedy. It's a sad song, but we sing it anyway. 'Cause here's the thing, To know how it ends, and still begin to sing it again, as if it might turn out this time, I learned that from a friend of mine.

And with that the entire stage looked just as it did in the opening. Enter Eurydice. Enter Orpheus. The story cycles - it begins again. Why? Because we will it to begin again, because maybe this time..

What would life be like if Juliet woke up before Romeo took the poison or if Odysseus’ crew had kept the wind bound up in its bag or if Orpheus had the confidence to keep walking forward? We know as audience members when we’re being sold a bill of goods. We can taste the sugar coating. Instead, give it to us straight. People get sick. We’re disappointed. We’re weak. We die. These are not things to deny, nor can we avoid them.

Rollins says that, “Art gets us to think about the hard things that are true.” And like I felt when I walked out of the theater yesterday, “allows us to feel satisfied in the dissatisfaction. We can enjoy the lack.” And when we can do that, we can handle the lack in our own lives when it strikes, perhaps not to enjoy it, but to bear it nonetheless.

Three totally random highbrow/lowbrow things I thought of reading this: Jakob Bohme (who we read for the Living School) and his belief that God birthed the cosmos because there was something God felt lacking in Him, and that God keeps creating because total fulfillment remains always just out of reach. Then, a line from a Bette Midler interview probably twenty-five years ago when she said that what kept her creative and working was so that she could buy shoes. And she said she never wanted to feel like she had enough shoes because then her fire might go out. Finally, the last season of THE GOOD PLACE, which I won't spoil for you if you haven't seen it.