“I’m thinking about Jesus. I’m thinking about Jonathan, and I’m thinking about Justice.”

That’s what my dear friend Sarah said to me after she read the previous version of this essay. I’ve rewritten this essay at least five times now, each time trying to step aside a bit more trying, as the poet Wendell Berry says, not to disturb “the silence from which it came.”

My impulse as a former philosophy major is to argue, to reason my way to Truth, but rhetoric doesn’t move people the way stories do. Jesus knew this. So did my friend Jonathan Smith.

Jonathan was more than the dad of two of my students. Jonathan and his wife Rochelle graciously invited me into their family. I mean who invites their kids’ theater teacher to your anniversary recommitment ceremony? The following year, I brought a small group of students up to Chicago where we stay at Jonathan’s childhood home, attended his father’s church and heard him preach. Jonathan and Rochelle invited me to speak at their daughter’s graduation party where I cried ridiculously, probably scared that I would lose connection with this family I had come not just to admire, but to love.

But I did not lose connection. We kept in touch. Jonathan was Vice President for Diversity and Community Engagement at St. Louis University. He was also a playwright, a poet and a musician. After Michael Brown was killed, even though his daughters had graduated and even though he had an entire college community to care for, Jonathan came back to my classroom to facilitate several discussions with students after they watched a shortened version of Amiri Baraka’s The Dutchman. I watched him all day guide these young people to see how the death of Black bodies should not be the inevitable outcome of even the most tenuous conflict. In hindsight, I can’t imagine how exhausted he was at the time, though he’d never let on.

But Jonathan always said yes. A few years later I was working on a podcast and I asked Jonathan if he would be willing to talk to me about Black Church music. We talked for a few hours where he told me stories of his childhood, growing up the son of a preacher in Chicago, like my dad, where music was the lifeblood of Sunday mornings. He introduced me to Snoop Dogg’s The Bible of Love album and why it is a brilliant reenactment of those Sunday morning rhythms.

The last time I saw Jonathan was during Covid lock down. I was talking to my friend Bess on one of those chat apps that everyone was using, and all the sudden there was Jonathan, coming in for a visit and a chat. We each had a cocktail in our hand and while we only talked for about fifteen minutes, we caught up and we laughed.

This weekend marks the one year anniversary of my dear friend’s passing. At 61, it was way too soon, but at 61 Jonathan had done the work of 20 men.

What Sarah reminded me after she read this essay was that the “silence from which it came” is truly Jonathan. Jonathan was a big dude with long dreads and the softest, most gentle voice that rarely spoke without the sound of a smile in it. He was brilliant. Nothing made him burst more than the equal brilliance of his wife and their three daughters.

But it is not for his brilliance, nor his soft spoken sweetness that Jonathan is the inspiration for this essay. It is for his willingness to hold me accountable when I needed to be held accountable. It was his youngest daughter’s senior year and we had just finished casting for the Student Run Musical. Jonathan called me and came directly into my office and he was fuming. He called me out. Had I seen the cast list, was I aware that the characters of the maid and the janitor had both been cast as Black students? No, I was not aware. I should have been, but I wasn’t. We talked for a long while. It was a good talk. We both learned things about each other. The crux of the conversation was that I became more aware of things I didn’t understand, and Jonathan learned that I understood perhaps a bit more than he realized. We had a loving, honest, hard conversation about race and as a White woman that was the first time in my life that had happened. That was the first time someone that didn’t look like me, loved me enough to be real with me. What a gift. That was fifteen years ago.

What I didn’t realize til just recently was just how special Jonathan’s gift was.

The Parable of the Vineyard Workers

About six weeks ago I was asked to write a blog article for my church on Jesus’ parable of the vineyard workers. I was honored to step out of my Prayer wheelhouse and speak to something a bit “meatier.”

In the midst of the time I spent studying the text, I happened to have two conversations with co-workers who talked to me candidly about what it is like to be a person of color working in White spaces. They were incredibly generous and vulnerable in revealing the trepidation they experience, the daily eggshells they step over, and the outright racism they encounter. Both also talked about knowing the boundaries they had to navigate to stay safely employed. Neither felt like they could speak freely and publicly in White spaces without risk of losing their jobs. (Read that last sentence again.) I don’t feel like it was an accident that I had these conversations fresh in my mind as I was studying Matthew 20.

This idea of being silenced had never occurred to me, partly because I’m naive and White, but also because there was a man in my life who was crazy enough to answer a call to teach White people in White spaces about Justice and Equity. This was truly Jonathan’s gift. “Loving people enough to hold us through our learning,” as my friend Sarah said.

At his memorial Rev. Starsky Wilson said, “Jonathan worked with gentleness and power to love people and institutions into their potential.”

But in the absence of Jonathan, who will speak up in White spaces? White people need to speak up in White spaces about Racism and systemic White Supremacy, and in churches we need to talk about its connection to White Christianity. Parenthetically, I don’t think White people like to admit there are such things as White spaces. White churches, White schools, White communities.

It feels important, though, that we name things accurately. This is, in part, what Jesus’ parable of the vineyard workers is about. Privileges - withheld and hoarded but also leveraged for the good of the beloved community. This is the term Dr. Martin Luther King Jr coined to describe where that arc towards justice is bending. This is what I wanted to write about.

Justice looks like beloved community.

This same idea is echoed in a NYT Op-Ed written last year by Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation, titled “Are You Willing to Give Up Your Privilege: Philanthropy alone won’t save the American dream”

If we, the beneficiaries of a system that perpetuates inequality, are trying to reform this system that favors us, we will have to give up something. Here are a few of the special privileges and benefits we should be willing to surrender: the intricate web of tax policies that bolster our wealth; the entrenched system in American colleges of legacy admissions, which gives a leg up to our children; and above all, the expectation that, because of our money, we are entitled to a place at the front of the line. - Darren Walker, NYT June 25, 2020

Walker is talking about the Divine Economy, talking about the American Dream as Beloved Community. He is telling the same story Jesus told two thousand years ago. He even echoes Jesus saying, “the last shall be first” when he challenges the notion that wealth entitles one to be in the front of the line.

So I wrote the blog piece, with fear and trembling, stumbling over my own biases and relying on the generosity of friends to check me. I’m still working on it, and I guess I can continue to keep working on it because the day it was supposed to be published, I received a note that said they were going in a different direction. No conversation. Just a Slack message.

So, I’m confronted with a gnawing question: do I stay in my lane?

Do I stick to writing about prayer? What would Jonathan advise me to do? Well, Jonathan would have me do the same thing Jesus would: spend time in silence, seek out the advice of wise people who love you, and finally, and always - speak the Truth in Love.

So here it is, the blog post that wasn’t…

Jesus said, “Nope, not today Karen.”

Stories are powerful business. Clarence Jordan, one of the founders of Habitat for Humanity said once, “Whenever Jesus told a parable, he lit a stick of dynamite and covered it with a story.” The best thing and the worst thing about a story is that it doesn’t tell us what to think. A good story raises questions rather than handing out easy answers. The story Jesus tells about the Workers in the Vineyard in Matthew is one of those stories that bring us nose deep into all kinds of questions.

Parable of the Workers: an overview Matthew 20: 1-16

Here’s the story: a land owner goes out to hire people to work the land. He hires people early in the morning, then again at nine, then again at noon, and when he notices at five that workers are still waiting for employment, he hires the rest late in the day. The workers he hires early in the morning agreed to work for one denarius. At the end of the day, all the workers, no matter what time they started, all earn one denarius. When the early morning workers see this, they complain saying that they deserve more than those who only worked an hour or even half a day. The landowner says he wants to pay everyone a fair wage and since the money is his, it is his to give out as he sees fit. He asks them, “are you envious because I’m generous?”

The interpretation we might have heard before is that God’s grace falls on everyone regardless of their merit. A person who has squandered their life on selfishness and yet at the end sees the error of their ways is just as deserving as the person who has dedicated their life to noble causes. Grace is freely given and cannot be earned.

We can also look at this story as a lesson on literal economic justice for migrant workers: the needs of the workers are given priority by the landowner, even over his own needs. Generosity trumps greed for the betterment of everyone. A commentary I read says, “After letting our imaginations dwell in the surprising generosity of this parable and of God, we can no longer look at that parking lot filled with farmworkers who are paid unjustly and who are viewed as disposable, and rest easy.”

God’s Abundance vs. Man’s Scarcity

I’d like to look at this parable from the perspective of the disgruntled workers and the story of Humanity’s grip on power. The perceived injustice from their point of view is just that, a perception that they are owed something more. They are grasping for what they believe is rightfully theirs.

And yet, Jesus is teaching us what the divine economy really is. It is living in God’s abundance rather than in human scarcity. To live in abundance is to live in both generosity and justice – to make sure that everyone has access to the things that we all value. To live in scarcity is to withhold and to hoard. And what we as humans withhold and hoard more than anything else is our privilege. But, when we live into God’s abundance, we give up the rules of privilege entirely. Privilege becomes something we leverage for the sake of a “beloved community” which Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. described as, “a community in which everyone is cared for, absent of poverty, hunger, and hate.” Notice that this community’s economy includes concrete goods like money and food but also includes the intangible goods of love and care.

Examples of Today: Who Suffers?

When we talk about curriculum in schools that teach the fullness of American history which includes the history and contributions of Black and Indigenous people of color, we are talking about abundance. But when white parents get up at Board of Education meetings and yell about “Critical Race Theory,” equity education, and the fear of their children “feeling badly about themselves,” isn’t this a form of hoarding and withholding? An implied belief that “my child’s right to feel comfortable is more important than your child’s right to be seen.” What feeds that sense of privilege?

In 2021, nineteen states enacted thirty-four laws restricting access to voting – far and away the most in any year in at least the past decade. Missouri was one of the first states to try and pass strict ID requirements fifteen years ago and was one of the states passing the suppressive law in 2021. We know these laws tend to impact people of color for a variety of reasons whether it be access to nearby polling places, limited flexible work hours, transportation, or other access issues. We also know that these laws limit voting power to those whose access to basic requirements like social security numbers, government issued IDs and other necessities to move within the system are challenging to obtain. Everyone has an equal right to vote. What feeds that sense that some are entitled to less?

When did equality start meaning less for me? And even if it does, can’t I do with less? Might I even do better with less?

For example, we’ve seen time and time again over the last several years whether it’s mask mandates or gun laws, the debates over balancing freedoms with public safety. A friend said to me today, “eventually our freedoms are going to kill us.” Like the vineyard workers, when we grasp for things we feel are rightfully ours to the detriment of our neighbor, we are not living in the fullness of the Kingdom of God.

Pastor Matt has talked about the sin of White Supremacy from the pulpit. In this parable, I think Jesus is talking about it as well. This is what feeds our sense of entitlement. This is what feeds our sense that our needs are more important than our neighbors’.

This is not somebody else’s sin. This is OUR sin. We have all felt entitled to things. We have all felt resentment towards someone that got something we wanted or angered that someone got something we felt they didn’t earn. But in God’s economy, there is no privilege. Instead, Jesus says, “Nope, not today Karen.”

That’s it.

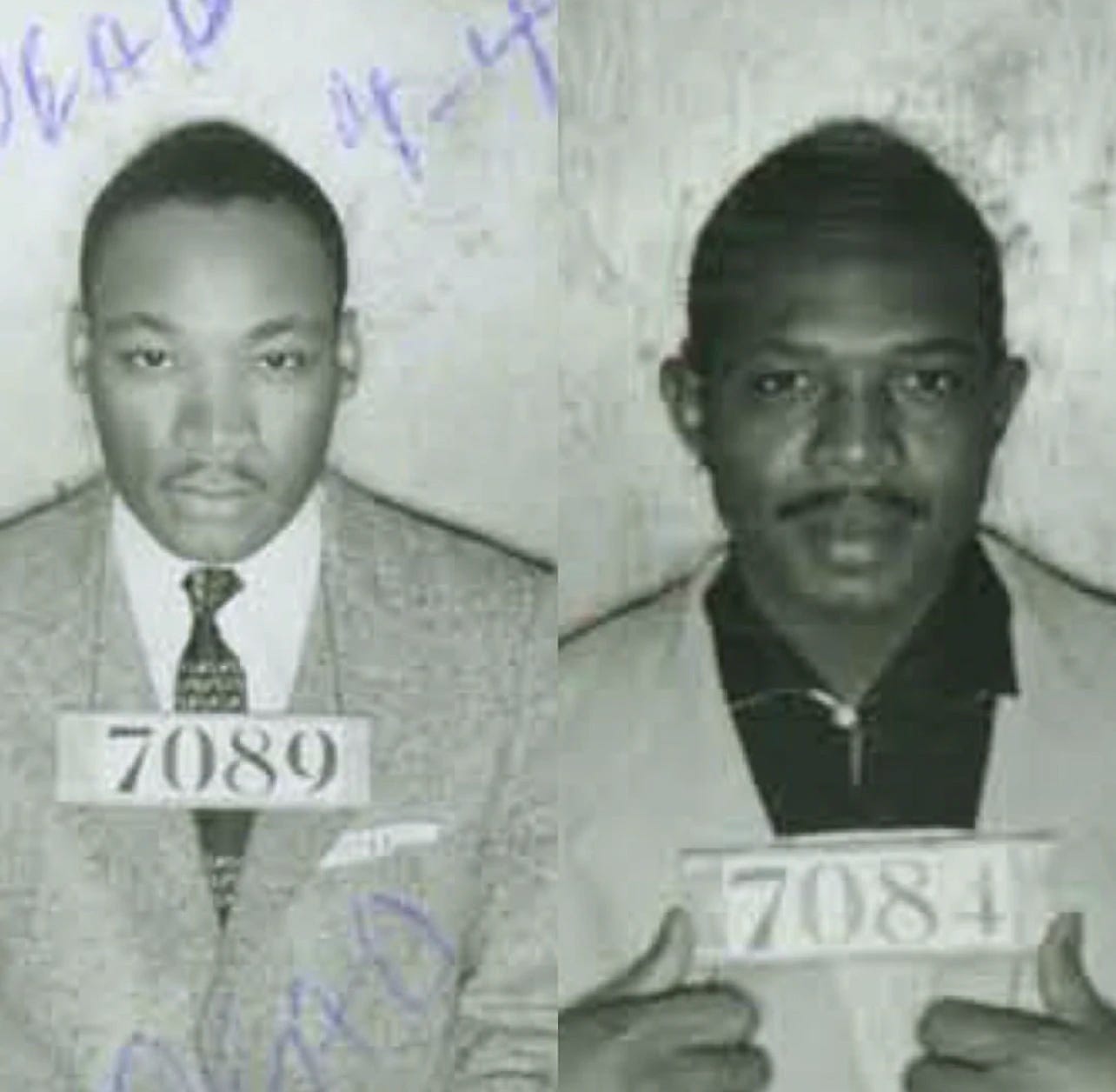

I don’t particularly see it as a radical message, just a True one. A message that Jonathan’s father dedicated his life to when he marched and got arrested with Dr. King in Montgomery in 1956.

A message that Jonathan dedicated his life instilling in not just the young people he worked with, thank God, but in everyone.

Sarah, whose life has been shaped by Jonathan and the Smith family said to me,“And what he gave up for it was his life. He answered the call to shape the institution on Juneteenth, 2016 and died Juneteenth 2021.

So. In Jonathan’s absence, what are White people doing to reduce the cost of Justice? What are they willing to do to heal enough, to be able to hear and have conversations about loving accountability? How will White people learn to love ourselves into our potential to truly be who we think ourselves to be - especially followers of Christ?”

Amen ❤️

Be well friends. Do good. - Kelley